Churches everywhere need help with faith and politics these days. On the one hand, partisan perspectives seep into our faith communities without us looking. There’s really nothing we can do about it. The animosity between “liberals” and “conservatives” is part of our culture. (I put them in quotation marks to remind us that these are labels, not people.) It’s impossible for “independents” and “centrists” to even state their politics without them. The opposition inherent in partisanship defines how people speak, think, and interpret any political statement or issue. It’s nearly impossible to navigate faith and politics without it.

Churches everywhere need help with faith and politics these days. On the one hand, partisan perspectives seep into our faith communities without us looking. There’s really nothing we can do about it. The animosity between “liberals” and “conservatives” is part of our culture. (I put them in quotation marks to remind us that these are labels, not people.) It’s impossible for “independents” and “centrists” to even state their politics without them. The opposition inherent in partisanship defines how people speak, think, and interpret any political statement or issue. It’s nearly impossible to navigate faith and politics without it.

Pastors and leaders can try to mitigate the tensions by reminding members to leave politics out of the pews and pulpit. They can try to keep church a safe place, reminding parishioners that the Gospel is neutral or knows no single party. And, to some degree, this is partially right.

The Gospel doesn’t align with any one party or political ideology exclusively. One way to interpret the history of Israel in the bible is to see it through this lens. Proper worship and faithfulness to God’s covenant can’t be reduced to one form of rule or ruler. Likewise, to allow God’s Word or will to be reduced to any one party, candidate, or ideology is equally objectionable. It would amount to idolatry.

The second commandment is clear that we’re allowed no images or representations for God…as if they were God. The effect of this commandment is far reaching. For people of faith, there no place the prohibition of images makes more sense than in the realm of politics. It holds theological truth and wisdom. No idea, image, or representation of God can replace the mystery of God and humility before faith in a living God. Reducing proper worship of God to belief in a political party, candidate, or ideology ultimately betray God and the heart of faith.

On the other hand, no disciple of Jesus can cooperate with the belief that the Gospel is not political. This is simply wrong scripturally, theologically, and historically. The Gospel is political and always was. Christianity has much to repent for in its politics. But, simply erasing its political dimensions and calling is not acceptable or desirable. The deep mystery of Christian spirituality and truth of faith in Christ only make sense when understood in political terms. Faith and politics are something every Christian must wrestle with like Jacob and the angel (Genesis 32:22-31). Jacob emerged from this wrestling as Israel, the name given to the people of God. (He was also in a bit of pain.) Faith cannot escape its relationship with politics, and it shouldn’t try.

On the other hand, no disciple of Jesus can cooperate with the belief that the Gospel is not political. This is simply wrong scripturally, theologically, and historically. The Gospel is political and always was. Christianity has much to repent for in its politics. But, simply erasing its political dimensions and calling is not acceptable or desirable. The deep mystery of Christian spirituality and truth of faith in Christ only make sense when understood in political terms. Faith and politics are something every Christian must wrestle with like Jacob and the angel (Genesis 32:22-31). Jacob emerged from this wrestling as Israel, the name given to the people of God. (He was also in a bit of pain.) Faith cannot escape its relationship with politics, and it shouldn’t try.

There is great temptation in Western Christianity to “spiritualize” faith, which essentially has meant to erase its concrete political, economic, and social meaning. But, this is nearly impossible. Terms like “Lord,” “Kingdom of God,” “Prince of Peace,” even “Christ” make little to any sense without understanding them in their historical political context, and understanding them explicitly as political terms.

The term politics is related to polis, which is the ancient Greek term for the city-state. This is where the term get its meaning for belonging to a people and land, and living under a rule or form of governance. Western politics is deeply influenced by political concepts that permeate biblical scripture such as the rule of law, sovereignty, and freedom.

The question is not whether Christian faith is political. Rather, the question is how is it political. What kind of politics does God require? What kind of politics does the Gospel make possible?  How do we interpret the Gospel’s invitation to live under the Lordship of Jesus as our true ruler and King? How do we interpret scripture regarding the purpose and fulfillment of creation – including all human relationships? What does Jesus’ life, ministry, death, and resurrection as Christ reveal to us regarding the way Christ’s community worships, lives, witnesses, and engages the world around it? These questions go to the heart of the Gospel and its politics.

How do we interpret the Gospel’s invitation to live under the Lordship of Jesus as our true ruler and King? How do we interpret scripture regarding the purpose and fulfillment of creation – including all human relationships? What does Jesus’ life, ministry, death, and resurrection as Christ reveal to us regarding the way Christ’s community worships, lives, witnesses, and engages the world around it? These questions go to the heart of the Gospel and its politics.

Ultimately, answers to these questions are not finally answerable. What I mean is that these are not abstract questions with answers that are frozen – once and for all – in time. Rather, these faith questions are essential for any disciple. Asking them and answering them is a faith-task that is ongoing.

Any church that proclaims Jesus Christ or his community on earth must ask and answer these questions as a simple matter of discipleship. In addition, Christians must ask them and answer them in the context in which they live their faith. Political issues surround us, which call for the church’s witness. The church must live out its own unique politics where it is. This is the call of the Gospel and Christian discipleship: to be Christ’s community in the world and witness to what God has made possible in the life, ministry, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

In the end, faith is not separate from politics. Quite the contrary, they two are intimately related to one another.

Christ’s community is called to cultivate its own politics. The church’s politics will be unique and related to, but ultimately different from, the world around it. Why? The church’s politics are founded on its best understanding of the Gospel. The Gospel, simply put, is the God’s revelation of love and grace for the world (this world). This is the proclamation of the Kingdom of God in Jesus Christ. In him, all can be reborn to see the truth of themselves, what new is life possible, the fulfillment 0f creation and reconciliation of human relationships. This is the Kingdom of God’s love and justice which the world has yet to fully know.

In addition, the church’s witness of faith draws it into the world of politics. In other words, God’s love for the world draws Christ’s body today into the world’s political issues. This includes its partisanship with all its tensions. Here, the church’s call is to the witness of Christ’s peace and justice in the work for a new humanity. This means the transformation of human relations and communion with the earth. In Christ, ethnic and racial differences, differences in station or class, even gender and sexual differences are no longer (Galatians 3:23-29) decisive. Likewise, partisan differences aren’t either.

What is decisive is the world God has made possible. For the prophets, just like for Christians, that has everything to do with politics. If Christian faith means anything today, it will find its expression in human politics. That’s the call and witness of the Good News.

Sadness is so easily pathologized. When it pops up unexpectedly or has no obvious reason, it can be quickly explained away as lurking depression or rejected as misplaced emotion. Sadness, however, may also be spiritual. Sadness is a regular, even healthy, part of life and companion of grief. Grief can be all around us in hurt relationships, lost values, declining communities, stress, elusive success, or deep-seated heartache from the past, which haunts our everyday life.

Sadness is so easily pathologized. When it pops up unexpectedly or has no obvious reason, it can be quickly explained away as lurking depression or rejected as misplaced emotion. Sadness, however, may also be spiritual. Sadness is a regular, even healthy, part of life and companion of grief. Grief can be all around us in hurt relationships, lost values, declining communities, stress, elusive success, or deep-seated heartache from the past, which haunts our everyday life. I’ve not posted for some time. But, Jeremiah called me back again. I needed some time for meditation.

I’ve not posted for some time. But, Jeremiah called me back again. I needed some time for meditation. In Chapter 5 of Jeremiah, the central theme moves from grief to judgment. There is a sense Israel and Judah are on trial. The emotions of anguish and anger that seem to drive chapters 1-4 begin to distill to negotiation and reason. There’s a reason to be angry. Again, theology – or making sense of God – accompanies makes sense of circumstance. The Book of Jeremiah was likely compiled while God’s people were already in Babylonian exile, as a witness and memory for the nation. In other words, it was compiled not in real time but after the fact. This means, the compilers have to make a sense of the people’s fate. Jeremiah’s prophecies, in this context, make perfect sense. He was right. It makes sense that Israel and Judah fell and were plundered because the nation had become corrupt. Verse 1 comes right out and says it:

In Chapter 5 of Jeremiah, the central theme moves from grief to judgment. There is a sense Israel and Judah are on trial. The emotions of anguish and anger that seem to drive chapters 1-4 begin to distill to negotiation and reason. There’s a reason to be angry. Again, theology – or making sense of God – accompanies makes sense of circumstance. The Book of Jeremiah was likely compiled while God’s people were already in Babylonian exile, as a witness and memory for the nation. In other words, it was compiled not in real time but after the fact. This means, the compilers have to make a sense of the people’s fate. Jeremiah’s prophecies, in this context, make perfect sense. He was right. It makes sense that Israel and Judah fell and were plundered because the nation had become corrupt. Verse 1 comes right out and says it:

The reality of the situation is also becoming apparent to Israel.

The reality of the situation is also becoming apparent to Israel. God obviously needs us. And, apparently, we need God.

God obviously needs us. And, apparently, we need God. Midst the scorn, there is also sorrow. Beneath the deepest anger, there is almost always grief. Grief is pain and loss. Perhaps God’s needs us more than we realize, and we need God. We just don’t really grasp that until we’re in trouble.

Midst the scorn, there is also sorrow. Beneath the deepest anger, there is almost always grief. Grief is pain and loss. Perhaps God’s needs us more than we realize, and we need God. We just don’t really grasp that until we’re in trouble.

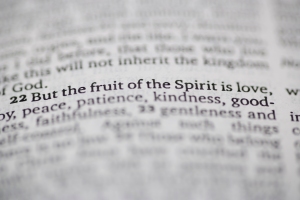

Paul’s understanding of the law and Christ is among the most important themes in Christian theology, especially Protestant theology. Paul first talks about this in Galatians 5. Paul is writing to a group of early Christian converts who apparently adopted or began teaching that you need circumcision to become a disciple of Jesus Christ. To know Paul is to know that Paul vehemently opposes this. Moreover, his opposition to it is central to understanding Christianity for Paul.

Paul’s understanding of the law and Christ is among the most important themes in Christian theology, especially Protestant theology. Paul first talks about this in Galatians 5. Paul is writing to a group of early Christian converts who apparently adopted or began teaching that you need circumcision to become a disciple of Jesus Christ. To know Paul is to know that Paul vehemently opposes this. Moreover, his opposition to it is central to understanding Christianity for Paul.

Since finishing my formal studies in 2010, I’ve been on a journey. First, I moved from Chicago to Graceland University, Lamoni, IA, to be the Director of Religious Life and campus minister in 2011. I’ve spent the last three years settling into this position: learning Graceland’s current institutional culture, getting to know the students who come to GU, developing the courses I’m teaching, and finding my alchemical vision for Christ’s mission and Community of Christ’s mission on campus. These responsibilities, and other denominational activities, have thoroughly absorbed the last three years of my life.

Since finishing my formal studies in 2010, I’ve been on a journey. First, I moved from Chicago to Graceland University, Lamoni, IA, to be the Director of Religious Life and campus minister in 2011. I’ve spent the last three years settling into this position: learning Graceland’s current institutional culture, getting to know the students who come to GU, developing the courses I’m teaching, and finding my alchemical vision for Christ’s mission and Community of Christ’s mission on campus. These responsibilities, and other denominational activities, have thoroughly absorbed the last three years of my life. I believe that living a whole spiritual life means responding to the s/Spirit within us that yearns to give birth to something. I call it “s/Spirit” because this fountain of life-giving and life-bearing energy is God’s Life and Creativity entwined indistinguishably with our own. It is a summons to live a life of freedom and creativity. That s/Spirit within us is the creative energy or vision, impulse of inspiration, and quietude of potential that haunts our working mind and resting moments. Paying attention to that s/Spirit at work within us leads us to what our spirituality is about.

I believe that living a whole spiritual life means responding to the s/Spirit within us that yearns to give birth to something. I call it “s/Spirit” because this fountain of life-giving and life-bearing energy is God’s Life and Creativity entwined indistinguishably with our own. It is a summons to live a life of freedom and creativity. That s/Spirit within us is the creative energy or vision, impulse of inspiration, and quietude of potential that haunts our working mind and resting moments. Paying attention to that s/Spirit at work within us leads us to what our spirituality is about. I think I just need

I think I just need